The past 100 years have seen two World Wars, the establishment of the NHS, three waves of feminist action, a number of governments and countless other events. But, what about when it comes to the law?

If you were to travel back in time to practice law as a solicitor or barrister in 1918, you would see significant differences. It’s safe to say the profession has become almost unrecognisable to that of the early 20th Century – with some changes for the better and others, arguably, for the worse.

Whether you’re a legal history buff or not, this article is for you! Read on to find out whether you would have made it as a lawyer 100 years ago.

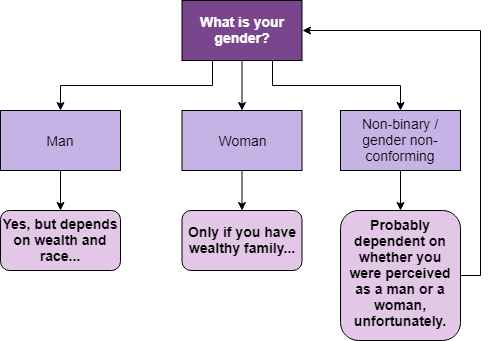

What’s Your Gender?

Way back in 1918, with World War One drawing to a close, the possibility of a woman being a barrister or solicitor was completely unheard of and could not be further from the Bar or Law Society’s contemplation.

So, in truth, the answer is no. If you are a woman (or perceived to be one), you probably wouldn’t have been able to practise as a lawyer – so you might want to hold off on jumping into that time machine.

But, if you visited just a few years later, you might have been in with a (slim) chance!

Here’s why:

Until the passing of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919, women were widely banned from attending university, never mind being a lawyer . With this Act, the prohibition on women in law was lifted.

In 1922, Ivy Williams of Inner Temple was called to the Bar, Carrie Morrison was the first woman to become a solicitor after passing her articles and, in the same year, Helena Normanton became the first woman to appear in court as an advocate.

Helena Normanton became a pioneer for female barristers and celebrated a long list of firsts, including becoming the:

- First woman to lead a murder trial

- First woman to obtain a divorce for her client

- And one of the first female King’s Counsel in 1949

Nevertheless, it is well worth remembering that these women were far from the norm; it was still quite remarkable for women to gain a university education, let alone continue on to become lawyers. Often, women had to rely on scholarships or family members who were willing to invest in their careers.

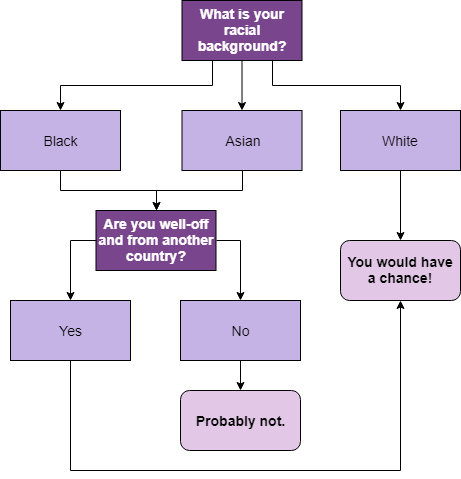

What’s Your Racial Background?

Alright, so, we’ve established that – for the most part – if you’re a woman, you probably wouldn’t be able to practise law in 1918. Which means … all men could, right? Wrong.

Although a handful of black and Asian men were called to the Bar in the latter half of the 19th century, including the likes of John Mensah Sarbah (the first Ghanaian barrister) and Monomohun Ghosh (the first Indian barrister), these men travelled from their home countries to study in the UK. This suggests they had access to enough money to do so – something less likely for black and Asian people living in Britain at the time.

Even if you surpassed oceans and financial requirements to be called to Bar, though, being a black or Asian barrister was not without its struggles.

In 1913, barristers were unable to dine at Gray’s Inn with their white counterparts – preventing them from accessing a type of qualifying session. And, in 1928, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru (India’s first Prime Minister) were disbarred from the Middle Temple for ‘agitation’ against British colonial rule.

It wasn’t until 1960s that the Society of Black Lawyers (formerly Immigrant, then Commonwealth Lawyers) was formed. Not to mention a Bar Race Relations Committee was only formed in 1982 to deal with racial and gender-based discrimination.

Nine years later, in 1991, Patricia Scotland became the first black female Queen’s Counsel, only serving to highlight the odds stacked against BAME people in the legal profession.

These days, more work is being done to ensure BAME people have access to legal careers.

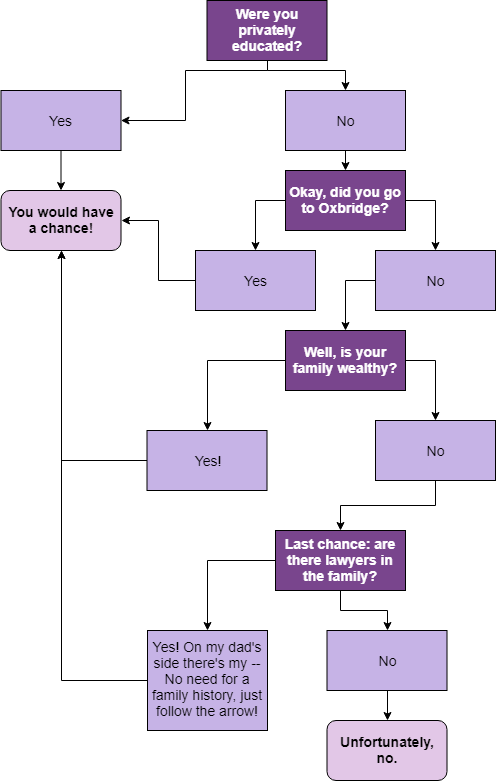

What’s Your Financial Situation?

Unfortunately, race and gender wouldn’t be the only barriers to you as a lawyer in 1918. There was also the issue of elitism.

Most advocates were Oxbridge-educated and from considerably wealthy backgrounds – arguably a trend which has barely improved in the 1900s and early 2000s.

Even now, over 70% of legal professionals come from this prestigious background. But that’s not to say things haven’t improved!

If you wanted to be called to and successful at the Bar, you would – to a large degree – have to rely upon social connections made early in life.

Your success in the early 20th century would rely on who your parents are and how much weight your surname carried in legal circles. A barrister could have his career fast-tracked simply because his father was an esteemed judge or barrister.

Nowadays, however, success is very much based on merit as opposed to reputation. So, family names will only get you so far, acting as no substitute for hard work and academic rigour.

However, even though historical stereotypes are on their way out, given that a private education and an Oxbridge degree often indicate you are at the pinnacle of education, it is understandable that the statistics somewhat remain.

So Would You Have Survived as a Lawyer 100 Years Ago?

Back in 1918 the legal profession also lacked many of the procedural safeguards and rules which are second nature in 2018.

It wasn’t until 1984 that the constabulary’s activity was regulated by the Police and Criminal Evidence Act.

Before then, lawyers could work cases on the basis of tenuous evidence and questionable tactics.

If you were strapped for cash, it wasn’t uncommon that you’d have to cope without defence counsel. Not to mention much of the trial was geared to the Prosecutor’s advantage.

Thankfully, this has changed significantly with well-established rules on the admissibility of evidence along with strict regulations on disclosure.

Overall, the criminal process in 2018 is much fairer and justice orientated that its 1918 counterpart which very much implemented an attitude of presumptuous guilt.

Clearly, the law has changed a lot over the last 100 years and the legal profession has had to adapt and keep pace.

Published: 09/03/18 Authors: Matthew Knights & Halimah Manan

Would You Survive as a Lawyer 100 Years Ago?

Like a Good Quiz? These Ones Are For You!

- Barrister vs Solicitor Quiz – Which One Are You?

- What Type of Law Firm Should I Apply to? Quiz

- Conversion to Law: Should I Convert to Law? Quiz